Go on, admit it. We love to complain about our public transport systems wherever we might be living. Even if they are the best of breed, they are still never quite good enough. They are either too slow, too crowded, too expensive or they are never on time.

What’s more, the bus stops, the taxi stands, or subway stations are never quite where we would like them.

Then we have the occasional breakdown in service that really gets commuters fuming. And the fares. Why do they only ever go up and never come down, regardless of the direction of energy prices? Do these companies think that we commuters are made of money?

Yes, public transport companies gets a lot of flak. But what would we do without them?

What are the alternatives? We conveniently forget that infrastructure can cost a lot to build, cost an arm and a leg to run and bags of cash to maintain.

But then, all that we ever see – or perhaps care about – might be why two 190 buses have just come and sped off in quick succession, and the next one doesn’t arrive for another eight minutes.

A can of worms

We tend to forget that public transport companies are no different to other businesses – they must be profitable. But some might argue whether they need to be.

If they are truly “public”, then why should be run for profit at all. That opens a can of worms about the allocation of public-sector finances, which is something that economists can debate to their hearts’ content. Point is, any business, must be profitable to be sustainable.

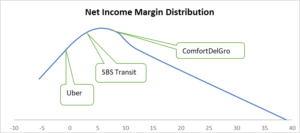

Generally, public transport companies do make profits. But the profits are not excessive. The median net income margin for 19 companies examined in this article is an unremarkable 4%. In other words, they only make $4 of bottom-line profit on every $100 of sales. Consequently, they can’t be accused of profiteering.

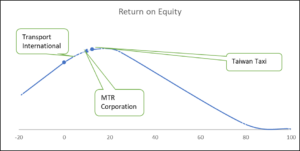

So, if they aren’t making excessive profits, how do we account for their relatively high returns on equity of 11%? From an investor’s perspective, a high return can be an attractive attribute. It means that they could generate $11 of profit on every $100 that we have invested in them.

So, if they can plough some of their cash flow back into their businesses, the money could grow at a desirable rate.

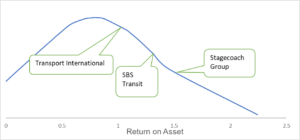

Part of the reason for their high returns on equity can be found in their efficient use of assets. On average, they generate about $70 of revenue on every $100 of asset employed.

Some of the highest include Singapore’s SBS Transit and the UK’s Stagecoach Group. The Go-Ahead Group generates more than a dollar of revenue for every dollar of asset employed in the business.

Another driver of the high returns on equity is leverage. They use other people’s money rather than their own money to fund the business.

They have on average about 50 times more in liabilities than assets, which is quite high. But the leverage can provide a powerful multiplier that, on average, has helped them double their return on equity. It compensate for their low net income margins.

Where’s the money

Many of these public transport operators pay dividends, though the payouts are, in general, not excessive. The median yield is just 2.4%. The payout appears to be adequately covered.

On average, they only distribute around a-third of their profits, which means that around 60% is retained for use within the business.

The retained profits could grow at around 11%, which would imply that public transport operators could grow their payout at 6% a year. Some have achieved that.

These include Singapore’s ComfortDelGro (SGX: C52) that has grown its dividends at a compound rate of 6.5% over the last five years, and Hong Kong’s MTR Corporation has also been able to beat the average.

Getting the right balance

From an investor’s perspective, public transportation companies could be sound investments because of their stable revenues and cash flows.

But the process of setting and adjusting public transport fares, which can be regulated, requires a delicate balance between affordability for commuters and the need to provide services that meet the demand of those same commuters.

There is also a never-ending need to improve and provide more services to cater for increasing population.

Whilst governments would like to provide funding for these services, it might be tough to do so in the long term. Public transportation companies will need to compete for funds with the demands from an ageing population and increasing healthcare costs.

Unfortunately, there is no easy solution because the funding issues are almost as broad and as deep as our MRT network.

So, the answer, perhaps, lies in looking for companies that could generate a decent return on equity, has a good track record of bottom-line profits and pays out some of those profits as dividends.

A version of this article first appeared in The Business Times.

None of the information in this article can be constituted as financial, investment, or other professional advice. It is only intended to provide education. Speak with a professional before making important decisions about your money, your professional life, or even your personal life. Disclosure: David Kuo does not own shares in any of the companies mentioned.