The world of finance and investing is full of wild facts and surprising things. Here are 11 of them, and their related lessons.

Note: This article was originally published on 29 October 2020 and updated on 2 February 2020.

1. Stocks with fantastic long-term returns can be agonising to own over the short-term.

From 1995 to 2015, the US-listed Monster Beverage (NASDAQ: MNST) topped the charts – its shares produced a total return of 105,000%, turning every $1,000 into more than $1 million.

But Monster Beverage’s stock price had also dropped by 50% or more from a peak on four separate occasions.

From 1997 to 2018, the peak-to-trough decline for Amazon.com (NASDAQ: AMZN) in each year ranged from 12.6% to 83.0%, meaning to say that Amazon’s stock price had experienced a double-digit peak-to-trough fall every year.

Over the same period, Amazon’s stock price climbed from US$1.96 to US$1,501.97, for an astonishing gain of over 76,000%.

Lesson: Volatility in the stock market is a feature, not a bug.

2. The stock price of a company that deals with commodities can fall hard even if the prices of the related-commodities actually grow.

Gold was worth A$620 per ounce at the end of September 2005. The price of gold climbed by 10% per year for nearly 10 years to reach A$1,550 per ounce on 15 September 2015.

An index of gold mining stocks in Australia’s market, the S&P / ASX All Ordinaries Gold Index, fell by 4% per year from 3,372 points to 2,245 in the same timeframe.

In 2015, oil prices started falling off a cliff.

The lowest price that WTI Crude reached in 2016 was US$26.61 per barrel, on 11 February. 10 months later on 21 December 2016, the price had doubled to US$53.53.

Over the same period, 34 of a collection of 50 Singapore-listed oil & gas companies saw their stock prices fall; the average decline for the 50 companies was 11.9%.

Lesson: The gap between a favourable macroeconomic event and a share’s price movement can be a mile wide.

3. Investors can lose money even if they invest in the best fund.

The decade ended 30 November 2009 saw the US-based CGM Focus Fund climb by 18.2% annually.

Sadly, the fund’s investors lost 11% per year over the same period. How? CGM Focus Fund’s investors chased performance and bailed at the first whiff of trouble.

Lesson: Timing the market is a fool’s errand.

4. Stock prices are significantly more volatile than the underlying business fundamentals.

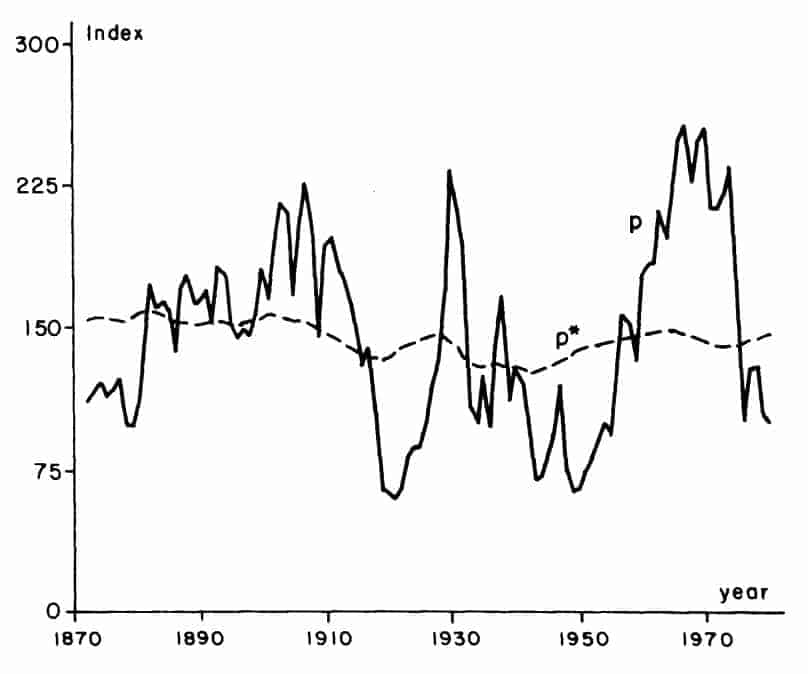

Nobel-prize-winning economist Robert Shiller published research in the 1980s that looked at how the US stock market performed from 1871 to 1979.

Shiller compared the market’s performance to how it should have rationally performed if investors had hindsight knowledge of how dividends of US stocks changed. The result:

The solid line is the stock market’s actual performance while the dashed line is the rational performance.

The solid line is the stock market’s actual performance while the dashed line is the rational performance.

Although there were violent fluctuations in US stock prices, the fundamentals of American businesses – using dividends as a proxy – was much less volatile.

Lesson: We’ll go crazy if we focus only on stock prices – focus on the underlying business fundamentals instead!

5. John Maynard Keynes was a great economist and professional investor. Interestingly, his early years as a professional investor were dreadful.

Finance professors David Chambers and Elroy Dimson published a paper in 2013 titled “John Maynard Keynes, Investment Innovator.”

It detailed the professional investing career of the late John Maynard Keynes from 1921 to 1946 when he was managing the endowment fund of King’s College at Cambridge University.

Chambers and Dimson described Keynes’ investing style in the early years as “using monetary and economic indicators to market-time his switching between equities, fixed income, and cash.”

In other words, Keynes tried to time the market. And he struggled. From August 1922 to August 1929, Keynes’ return lagged the British stock market by a total of 17.2%.

Keynes then decided to switch his investing style. He gave up on trying to time the market and focused on studying businesses.

This is how Keynes described his later investing approach:

“As time goes on, I get more and more convinced that the right method in investment is to put fairly large sums into enterprises which one thinks one knows something about and in the management of which one thoroughly believes.”

Chambers and Dimson’s paper provided more flesh on Keynes’ business-focused investing style.

Keynes believed in buying investments based on their “intrinsic value” and that he preferred stocks with high dividend yields.

An example: Keynes invested in a South African mining company because he held the management team in high-regard and thought the company’s stock was selling at a 30% discount to his estimate of the firm’s break-up value.

So what was Keynes’ overall record? From 1921 to 1946, Keynes beat the British stock market by eight percentage points per year.

When he tried to time the market, he failed miserably; when he started investing based on business fundamentals, he gained stunning success.

Lesson: Invest by looking at stocks as pieces of businesses – it’s an easier route to success.

6. Having extreme intelligence does not guarantee success in investing.

The hedge fund Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) was staffed full of PhDs and even had two Nobel Prize winners, Myron Scholes and Robert Merton, in its ranks.

Warren Buffett even said that “If you take the 16 of them [in LTCM], they probably have the highest average IQ of any 16 people working together in one business in the country, including Microsoft or whoever you want to name – so incredible is the amount of intellect.”

LTCM opened its doors in February 1994.

The firm eventually went bust a few years later. One dollar invested in its fund in February 2014 became just 30 cents by September 1998.

In 2009, Andrew Lo, a finance professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, started his own investment fund in the US.

2009 was the year when many major stock markets around the world bottomed after the global financial crisis started a few years earlier.

Lo’s fund gained 15% in 2010, but then lost 2.7% in 2011, 7.7% in 2012, and 8.1% in 2013. The fund was shut in 2014. The S&P 500 in the US nearly doubled from the start of 2009 to the end of 2013.

Larry Swedroe’s book, The Quest for Alpha: The Holy Grail of Investing, described the track record of MENSA’s investment club in the US.

MENSA’s members have IQs in the top 2% of the global population. In the 15 years ended 2001, the S&P 500 gained over 15% per year, while MENSA’s US investment club returned just 2.5% per year.

Lesson: Warren Buffett once said, “You don’t need to be a rocket scientist. Investing is not a game where the guy with the 160 IQ beats the guy with 130 IQ.”

It’s more important to invest with the right investment framework and have control over our emotions than it is to have extreme intelligence.

7. A stunning number of stocks deliver negative returns over their entire lifetimes.

A 2014 study by JP Morgan showed that 40% of all stocks that were part of the Russell 3000 index in the US since 1980 produced negative returns across their entire lifetimes.

JP Morgan defined “lifetime” as the “time when the company first exists in public form and reports a stock price, and until its last reported price in 2014 or until the date at which it was merged, acquired or for some other reason delisted.”

Lesson: Given the large number of stocks that deliver losses to investors, implementing a robust investment framework that helps to filter out potential losers can make a big difference to our investing results.

8. Going against the herd can actually cause physical pain.

Psychology researchers Naomi Eisenberger, Matthew Lieberman, and Kipling Williams once conducted an experiment whereby participants played a computer game while their brains were scanned.

The participants were told they were playing the game with two other people when in fact the other two were computers.

The computers were programmed to exclude the human participant after a period of three-way play.

During the periods of exclusion, the brain scans of the human participants showed activity in the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula. These are the exact areas of our brain that are activated by real physical pain.

Investor James Montier recounted the experiment in his book The Little Book of Behavioral Investing and wrote: “Doing something different from the crowd is the investment equivalent of seeking out social pain.”

Lesson: Investing is not easy, especially when there’s a need to go against the crowd. Make plans to deal with the difficulties.

9. One of Warren Buffett’s best long-term investments looked like a loser in the first few years.

Buffett started buying shares of the Washington Post Company (now known as Graham Holdings Company) in 1973 and spent US$11 million in total.

By the end of 2007, Buffett’s Washington Post stake had grown by more than 10,000% and was worth US$1.4 billion. By all accounts, Buffet’s Washington Post investment was a smashing success.

But here’s the kicker: The Washington Post’s stock price fell by 20% after Buffett’s investment and stayed at that level for three years.

Lesson: Great investments take time to play out. Be patient!

10. It’s easier to make long-term predictions for the stock market than short-term ones.

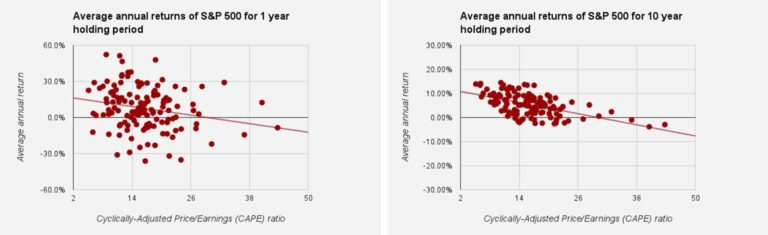

Source: Robert Shiller’s data; author’s calculation

The two charts above use data on the S&P 500 from 1871 to 2013.

They show the returns of the S&P 500 against its starting valuation for holding periods of 1 year (the chart on the left) and 10 years (the chart on the right).

The stock market is a coin-toss with a holding period of 1 year: Cheap stocks can fall just as easily as they rise, and the same goes for expensive stocks.

But a different picture emerges when the holding period becomes 10 years: Stocks tend to produce higher returns when they are cheap compared to when they are expensive.

Lesson: Invest with a long time horizon because we can make better predictions and thus increase our chances of success.

11. Simple investment strategies often beat complex ones.

Investment manager Ben Carlson wrote in 2017 that the investment performance of US college endowment funds couldn’t beat a simple strategy of investing in low-cost index funds.

For the 10 years ended June 2016, the US college endowment funds with returns that belonged to the top-decile had average annual returns of 5.4%. Carlson described the investment approach of US college endowment funds as such:

“These funds are invested in venture capital, private equity, infrastructure, private real estate, timber, the best hedge funds money can buy; they have access to the best stock and bond fund managers; they use leverage; they invest in complicated derivatives; they use the biggest and most connected consultants…”

In the same 10-year period, a simple portfolio that Carlson named the Bogle Model (after the late index fund legend John Bogle) produced an annual return of 6.0%.

The Bogle Model consisted of three, simple, low-cost Vanguard funds: The Total US Stock Market Index Fund (a fund that tracks the US stock market), the Total International Stock Market Index Fund (a fund that tracks stocks outside of the US), and the Total Bond Market Index Fund (a fund that tracks bonds).

The Bogle Model held the three funds in weightings of 40%, 20%, and 40%, respectively.

Lesson: Simple investing strategies can be really effective too. Don’t fall for a complex strategy simply because it is complex.

12. Buying and holding beats frequent trading.

Jeremy Siegel is a finance professor from Wharton, University of Pennsylvania and the author of several great books on investing.

In 2005, he published a book, The Future For Investors.

Wharton interviewed him to discuss the research for the book, and Siegel shared an amazing statistic (emphasis is mine):

“If you bought the original S&P 500 stocks, and held them until today—simple buy and hold, reinvesting dividends—you outpaced the S&P 500 index itself, which adds about 20 new stocks every year and has added almost 1,000 new stocks since its inception in 1957.”

The S&P 500 is not a static index. Many stocks have been added to it while many stocks have also removed.

So, we can also see the S&P 500 as a ‘portfolio’ of stocks that have experienced very active buying and selling.

What Siegel discovered was that over a period of nearly 50 years, a long-term buy-and-hold ‘portfolio’ of the original S&P 500 stocks would have outperformed the actual S&P 500 index that had seen all that relatively frantic ‘trading’ activity.

Lesson: Active trading is bad for our returns. To do well in investing, patience is an important ingredient.

13. It’s incredibly difficult to make money by trading currencies

The Autorité des Marchés Financiers (AMF) is the financial regulator in France – think of them as the French version of the Monetary Authority of Singapore.

In 2014, the AMF published a study on individual forex traders. It looked at the results of 14,799 individual forex traders for a four-year observation period from 2009 to 2012 and found some astonishing data:

- 89% of the traders lost money

- The average loss was €10,887 per trader

- The total loss for the nearly 15,000 traders was more than €161 million

Lesson: Trading currencies could be a faster way to lose money than lighting your cash on fire.

14. Historically, the longer you hold your stocks, the lower your chances of losing money

Based on data for the US stock market from 1871 to 2012 that was analysed by Morgan Housel, if you hold stocks for two months, you have a 60% chance of making a profit.

Stretch the holding period to 1 year, and you have a 68% chance of earning a positive return. Make the holding period 20 years, and there’s a 100% chance of making a gain.

The chart below, from Morgan, illustrates these:

Lesson: Time in the market is your best ally.

15. Huge moves in stocks that should not have happened, according to mainstream finance theories, have happened

In 12 August 2019, Argentina’s key stock market benchmark, the Merval Index, fell by a stunning 48% in US-dollar terms. That’s a 48% fall. In. One. Day.

According to investor Charlie Bilello, the decline was a “20+- sigma event.” Mainstream finance theories are built on the assumption that price-movements in the financial markets follow a normal distribution.

Under this framework, the 48% one-day collapse in the Merval Index should only happen once every 145,300,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 years.

For perspective, the age of the universe is estimated to be 13.77 billion years, or 13,770,000,000 years.

Lesson: The movement of prices in the financial markets are significantly wilder than what the theories assume. How then can we protect ourselves? Bilello said it best: “We must learn to expect the unexpected and be prepared for multiple outcomes, with diversification serving as our best defense.”

16. Timing the market based on recessions simply does not work

In an October 2019 blog post, investor Michael Batnick included the following chart:

The red line shows the growth of $1 from 1980 to late 2019 if we bought US stocks at the official end-date of recessions, and sold stocks at the official start-dates.

A $1 investment became $31.52, which equates to an annual return of 9.3%. That’s not too shabby.

But if we had simply bought and held US stocks over the same period, our dollar would have grown by 11.8% per year to become $78.31. That’s a significantly higher return.

Lesson: Trying to side-step recessions can end up harming our returns, so it’s far better to stay invested and accept that recessions are par for the course when it comes to investing.

17. The market is seldom average

Data from Robert Shiller show that the S&P 500 had grown by 6.9% per year (after inflation and including dividends) from 1871 to 2019.

But amazingly, in those 148 years, only 28 of those years showed a return of between 0% and 10%. There were in fact 74 years that had a double-digit gain, and 23 years with a double-digit decline.

The chart below shows the frequency of calendar-year returns for the S&P 500 from 1871 to 2019:

Lesson: Market returns are rarely average, so don’t expect to earn an average return in any given year. Don’t be surprised too and get out of the market even if there has been a big return in a year.

Looking for investment opportunities in 2022 and beyond? In our latest special FREE report “Top 9 Dividend Stocks for 2022”, we’re revealing 3 groups of stocks that are set to deliver mouth-watering dividends in the coming year.

Our safe-harbour stocks are a set of blue-chip companies that have been able to hold their own and deliver steady dividends. Growth accelerators stocks are enterprising businesses poised to continue their growth. And finally, the pandemic surprises are the unexpected winners of the pandemic.

Want to know more? Click HERE to download for free now!

Follow us on Facebook and Telegram for the latest investing news and analyses!

The Smart Investor is not licensed or otherwise regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore, and in particular, is not licensed or regulated to carry on business in providing any financial advisory service.

Accordingly, any information provided on this site is meant purely for informational and investor educational purposes and should not be relied upon as financial advice. No information is presented with the intention to induce any reader to buy, sell, or hold a particular investment product or class of investment products. Rather, the information is presented for the purpose and intentions of educating readers on matters relating to financial literacy and investor education. Accordingly, any statement of opinion on this site is wholly generic and not tailored to take into account the personal needs and unique circumstances of any reader. The Smart Investor does not recommend any particular course of action in relation to any investment product or class of investment products. Readers are encouraged to exercise their own judgment and have regard to their own personal needs and circumstances before making any investment decision, and not rely on any statement of opinion that may be found on this site.

Note: An earlier version of this article was published at The Good Investors, a personal blog run by our friends.

Disclosure: Chong Ser Jing owns shares of Amazon.